Breach of principles of growing a society from the base, through agriculture and cottage industry, has seen a highly abrasive economy that lacks soul and compassion

By Prem Prakash

- Kumarappa established the necessity of agriculture and cottage industry in Gandhi’s non-violent economic principles

- welfare-oriented development advocated by economists like Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze can be traced back to Kumarappa

- In the age of vertical growth, the quilt of development did not only become costlier but also shrunk in size

- frightening picture is of the farmers committing suicide and poor people raising an accusing finger at the liberalised economy

AT the time when global society is doomed to carry the burden of devastating chemical warfare and deafening bullets after a catastrophe pandemic, we remember Mahatma Gandhi, who spoke of human dignity in every context, from swaraj to individual to society. And for him, the touchstone of human dignity was always the same – non-violence and the last man. Therefore, it would be interesting to note what light Gandhi’s economic view can shed on the race for development.

A time which has been described by veteran journalist Prabhash Joshi as the “Golden Age of Grand Consumption” is witness to movements at the national and international levels for the protection of human rights and struggles are taking place, dark narratives about the prevalence of human dignity and self-respect are also being written in the same period.

NON-VIOLENCE ECONOMY

Before we go further on this track, it has to be made clear that Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence cannot be separated from his economic ideas. His is a balanced view, where on the one hand he tests the question of human dignity on a rigorous basis, and on the other he broaches on self-restraint, self-discipline and co-existence. As he said, “I must confess that I do not draw a sharp or any distinction between economics and ethics. Economics that hurt the moral well-being of an individual or a nation are immoral and, therefore, sinful. Thus the economics that permit one country to prey upon another are immoral. It is sinful to buy and use articles made by sweated labour.” (YI, 13-10-1921, p. 325)

Gandhian economist JC Kumarappa’s ‘The Economy of Permanence’ is considered as a bible for those economists who believe in the life-principles of non-violence

In a modern age, which is dazzled by sexuality, success and sensex, a discussion on Gandhian criterion is sure to sound like a sermon, and has no inclination to consider its practicality either at the mental or intellectual levels. It is for this reason that Gandhi’s vision of national construction has been described by his critics even in his lifetime as impractical and idealistic.

Gandhi’s economic ideas were generally not taken seriously. But this was not the real case. As a matter of fact, those who disregarded the Father of the Nation’s ideas were the people who found it important to be walking in the corridors of power. The power of the rulers does not strengthen democracy nor does it help achieve anything beneficial to the people. It is for this reason that immediately after Independence, Gandhi spoke of disbanding Congress and he suggested that members of Congress should turn towards villages and they should devote their energy to building ‘Gram Swaraj’.

Well known Gandhian economist JC Kumarappa’s ‘The Economy of Permanence’ is considered as a bible for those economists who believe in the life-principles of non-violence. In the very first chapter of the book, Kumarappa explodes the myth that the economy and development can never be stable. Our experience from industrial revolution to liberalisation shows that the scope of development and its criteria keep changing.

On the same basis, the government and society too keep shuffling the priorities regarding economy and development. But no serious thought has emerged with regard to the ultimate goal of this constant change. The only idea that has emerged time and again is that only the powerful will succeed and survive. The ideological maxim in the economic vocabulary for this thinking is “survival of the fittest”. It can be seen what place there is for human compassion and dignity in this worldview. This is the violent vision of prosperity and development. It is a view which tramples others under its boot and moves ahead by lashing out at others.

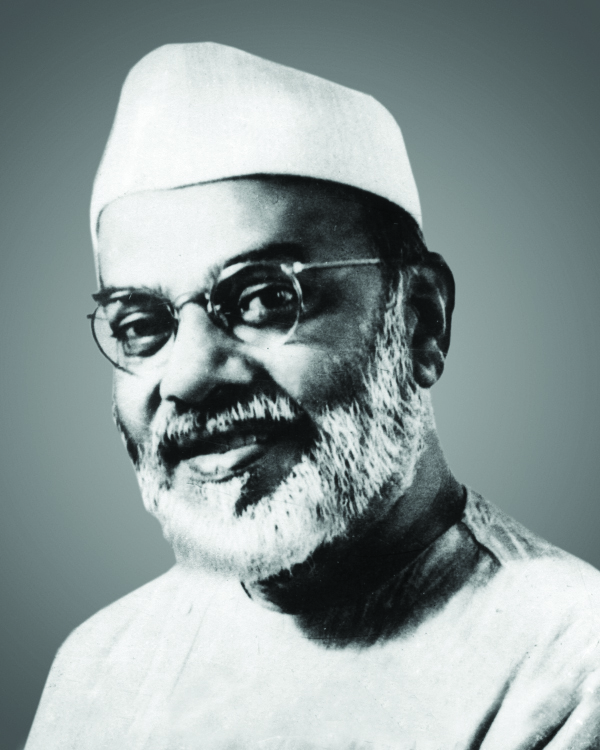

JC Kumarappa (born Joseph Chelladurai Cornelius), who later went on to become the greatest exponent on applying Gandhian values to economics. Kumarappa was an Indian Christian satyagrahi, a relative rarity, and he pronounced a devastating indictment of his co-religionists for siding with the British.

DEVELOPMENT CRITIQUED

It is not the case that there has not been any criticism of this violence-ridden development. Non-political groups, thinkers and awareness groups from America to India joined hands to point out that the logic of globalisation that gathered force at the end of the Cold War and became the official policy of governments should not be at the cost of human dignity and the disregard of the environment.

The welfare-oriented development advocated by economists like Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze can be traced back to the thinking of Kumarappa. This takes us near Gandhi but not to Gandhi directly. This is not a strategy to keep Gandhi away from the economic polemics. Sudhir Chandra, who comments on Gandhi and his values for our times, sees this abstinence as an “Impossible Possibility”, which is also the name of the book Sudhir Chandra wrote on Gandhi.

It is not possible to go to Gandhi half-heartedly because here is a man who invites people by lighting the lamps of truth, love and kindness because we will be tied down by all the touchstones, because in Gandhi’s eyes these are the supreme criteria for testing human dignity. To understand this contradiction and to talk about development, self-discipline and livelihood in the light of Gandhian economic principles, there is no better way of doing that than to get back to Kumarappa.

Kumarappa in his work, “The Economy of Permanence” clearly states that unless at the devolutionary level possible self-restraint is not translated into a solid structure, it will not be possible to attain economic empowerment in the country. In India’s village traditions, co-existence and self-restraint go hand in hand. Unfortunately, those who see development in the light of urbanisation do not see this natural complementariness of the village economy or refuse to appreciate its critical importance.

RURAL LUXURIES

The village life that has seen its manner of language and its manner of use of water change in a few miles radius for centuries is keenly aware that its basic needs and goals have to be realistic. Shunning greed and frugality is part of the nature of village life. Unfortunately, instead of expressing happiness over this, frugality is considered as something that is not part of the mainstream. As a consequence, the desire for lavishness has spread in villages, which once considered self-restraint as the art of living.

Gandhi in ‘Hind Swaraj’ had staunchly opposed big costs, bulk production and mechanisation. In Kumarappa’s words, it is necessary that life, culture and basic goals should remain interlinked so that risks of an uncertain state of affairs are contained. It is for this reason that Kumarappa talks of the economy of permanence.

Kumarappa’s economics is based on the principle of giving every individual of independent India economic self-reliance and all-round development. Kumarappa is one of the rare economists who was an advocate of the natural village economy and who believed that protection of the environment was of far greater importance than industrial-commercial progress.

Though wealth and sensitivity are two different things today, it is not possible to reach one with the other. But in Gandhi’s view, it is to determine the path from ‘Swaraj’ to ‘Swadeshi’ to ‘Self-restraint’

It is seen from historical evidence that even in his own time, Gandhi’s colleagues did not fully agree with his economic vision. This is why later there could never be an agreement between independent India’s economic policies and that of Gandhi’s. The situation was such that due to blind imitation of Western economic models, economic theorists like Kumarappa were soon forgotten.

Gandhi, on the contrary, had felt deeply during the freedom struggle that British subjugation and exploitation has blown to pieces the Indian way of reconciling its many ways of living. Under the pressure of the colonial economic system, Indian farmers and the land were being used to satisfy the greed of foreign consumers. The same greed has today assumed the post-modern frenzy.

GRAM SWARAJ

The backbone of the gram swaraj that Gandhi spoke of was agriculture and cottage industries. This was given the name of a devolved economy. Gandhi had seen in the agriculture system the seeds of eternal self-restraint. Why would this not be, because Gandhi, when he returned from South Africa, went to villages and stood with the farmers. Champaran Satyagraha is an example of the fact that what Gandhi saw in the farmer was the heroic soldier of nonviolence of the India of his dreams, and not just a mere herdsman and producer of a fistful of food grains.

Kumarappa came to Gandhi after completing his economic studies abroad. It is worth noting that while studying general economics at Columbia University, he wrote a research paper under the guidance of well-known economist Edwin Seligman, titled “India’s general economy and poverty”. In this, he studied the reasons for India’s economic distress and discovered that British colonial policies harmed Indian economic interests.

It is in the course of this study that Kumarappa found that the main reason for India’s pitiable economic state was British colonialism and its unethical and oppressive policies. When he met Gandhi on his return to India, the latter explained to him the necessity of self-discipline for agriculture and cottage industries.

What Gandhi had to say was already close to the thinking of Kumarappa, but it also answered many of the questions that had earlier puzzled him. It is evident that he was influenced deeply by Gandhi. Later, he established the necessity of agriculture and cottage industry in Gandhi’s non-violent economic principles, in which exploitation was replaced by cooperation, and he recognised minimum needs rather than consumerism as the right criterion.

It was not only possible to attain a stable economy of self-restraint through cooperation and satisfaction of minimum needs, but it also serves as a protection from the dangers of natural disturbances.

COOPERATION NOT COMPETITION

The Gandhian view of looking at cooperation instead of competition where development and life-values are not viewed separately but together. It is for this that when urban consumption rose and imports became necessary, there was a demand for farmers, who were offered the lure of exports and increased earnings. Kumarappa not only opposed this but he was prepared to launch a protest against it.

He felt that this would clearly make the devolved economy into a dependent system and farmers and workers would become victims of exploitation. It is not necessary to reiterate how Kumarappa’s apprehension of that time has become a frightening reality of today.

Shunning greed and frugality is part of the nature of village life. Unfortunately, instead of expressing happiness over this, frugality is considered as something that is not part of the mainstream

People who prepare the stage for the concentrated capital of the private sector have little concern for the need to extend the helping hand to reach the people, the confidence and the right to fulfil their responsibilities on their own strength. The reason behind the slogan of inclusive growth is because in the age of vertical growth, the quilt of development did not only become costlier but it also shrunk in size, leaving out a large section of the population of the country outside its spread.

The frightening picture is of the farmers committing suicide and poor people raising an accusing finger at the liberalised economy. People who see the dignity of the citizen in terms of a consumer should be asked the question as to why the rupee and the dollar were more or less of the same value at the time of independence, and why was the path of welfare economics given up for the sake of wayward private capital’s path? Is it not an expression of ‘no confidence’ in a country of large workforce and its prowess that progress cannot be achieved through them?

ILLUSIVE NEW INDIA

Today the meaning of “New India” means that India is the biggest market in the world. Today an Indian’s identity is that of a consumer and a worker who can be hired for a cheap wage. Surprisingly, even those revolutionary individuals and groups who file petitions against the government in the name of human dignity and human rights have no realisation as to the reason for this pathetic state of affairs.

If today anyone has an answer to this mind-boggling question it is only Gandhi, and his non-violent worldview. A view which throws an amulet around our necks that if we have any doubt, any apprehension then we have to remember the last man and decide whether our policies will help improve his life, whether it will bring any happiness to him. If the answer is yes, then there is no need to hesitate to follow the policy. But if the answer is no, then it should be realised that what we want to see is not just harmful to us but to everyone else.

Though wealth and sensitivity are two different things today, it is not possible to reach one with the other. But in Gandhi’s view, it is to determine the path from ‘Swaraj’ to ‘Swadeshi’ to ‘Self-restraint’. It is this determination that Gandhi’s favourite economic thinker Kumarappa has given the logic of making permanence a credible underpinning. In a country where 54 per cent of resources are under the control of the billionaires (New World Wealth Report 2016) and where 7.30 crore people (Brookings Report 2018) are not only poor but are forced to live in dire conditions, it is Gandhi’s economics that provides honest and humane way out.