The opposition huddle is still a huddle. The anti-Modi sentiment is the only glue holding them together. But that may not be sufficient to defeat Modi and the BJP in 2024. There is a need for a credible political and economic agenda

By Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr

- The desire to defeat Modi is quite strong in all of the 15 political parties, though their strengths and the intensity are of varying degrees

- NCP’s Sharad Pawar and JD (U)’s leader and Bihar CM Nitish Kumar are seasoned politicians and are not interested in ideological opposition to Modi

- Tamil Nadu CM and DMK supremo M K Stalin belongs to a party which will not mind allying with the BJP if the power equation favours him

- For the first time in three years the Reserve Bank of India has expressed concern over inflation in the country, and that cannot be good news for Modi

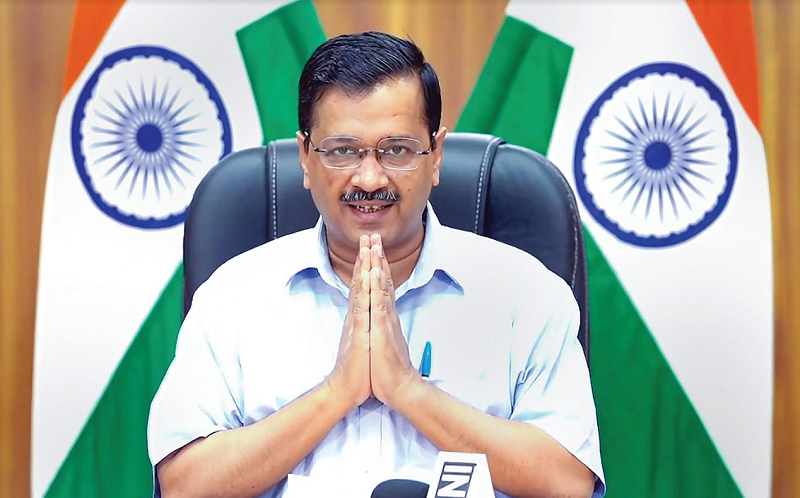

THE June 23, 2023, all-opposition party conclave in Patna, which gathered nearly all of the anti-BJP parties, with Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) at one end and the Congress at the other, has not yet emerged as a united front which will fight the 2024 Lok Sabha election to defeat Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP. They are to meet again in Bengaluru in the second week of July 2023. The desire to defeat Modi is quite strong in all of the 15 political parties, though their strengths and the intensity of their dislike for the politics of Narendra Modi and the BJP are not of the same degree. And their motivations differ too. The Congress is opposed to the BJP because it wants to regain its status as a dominant party across India and be the party of governance at the Centre. So, the motivation of Congress against the BJP is strategic. Congress professes to believe in secularism, but it does not fight shy of playing footsie with communalists all around – Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and Sikh without abandoning its rhetorical and political commitment to secularism. AAP on the other hand is a strongly Hindu-minded party under the garb of nationalism like the BJP but AAP leader and Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal is fiercely ambitious like Prime Minister Modi. If there is anyone who really wants to be the PM it is Kejriwal, not Rahul Gandhi, not Nitish Kumar. That is why, political observers are sceptical of the opposition parties who want to defeat Modi but there is nothing else that unites them. But the anti-Modi sentiment may not be the strong force sufficient to defeat Modi in the parliamentary elections.

THE CHALLENGE OF SELECTING A LEADER

The debating point in the media about a united opposition against Modi is about the Prime Ministerial face of the combined opposition, and it looks like that agreement on the issue is going to be a difficult one. The Congress has no doubt that it has the right to the Prime Minister’s post and the best man for the job from the party is Rahul Gandhi. Though it is true that all other parties in the anti-BJP opposition cannot claim to be national parties with a footprint across the country, they are not willing to accept Congress as the leading party. Their reluctance to accept Congress or Gandhi as the leader is justified by looking at the number of seats that Congress has in the Lok Sabha, 44 in 2014 and 53 in 2019. But the fact is that even with its hugely reduced numbers in Parliament, it remains the single largest party. In terms of sheer numbers, Congress has the rightful claim to the Prime Minister’s post. But then, the argument goes, the other parties would not want to work hard to defeat the BJP to hand over the political crown, as it were, to Congress. The argument against Congress as the claimant to the prime minister’s post is not strong enough if the logic of numbers is to be followed. It would seem that if things go well for the opposition, they would concede the Congress’ claim if the Congress emerges as the single largest party in the opposition ranks even if it does not cross the 100-seat mark. This is an easier issue to solve after the elections because the numbers that each party commands become clear and there would not be too many arguments.

AAP is a strongly Hindu-minded party under the garb of nationalism like the BJP but AAP leader and Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal is fiercely ambitious like PM Modi. If there is anyone who really wants to be the PM it is Kejriwal, not Rahul Gandhi, not Nitish Kumar

The crucial issue is whether the opposition should have a prime ministerial candidate going into the 2024 election. This can be a tricky question. If the opposition were to agree to the Congress’ demand of naming Rahul Gandhi as the prime ministerial candidate, there will be scepticism both in the opposition ranks and in the general public about whether Rahul Gandhi is strong enough to be pitched against an entrenched and popular Narendra Modi. The BJP is only too keen for a Rahul Gandhi versus Modi contest because heavyweight Modi is assumed to have an advantage. Many would say that Rahul Gandhi is not the political weakling he was in 2019 and that post-Bharat Jodo Yatra he has been transformed into a credible people’s leader. But the jury is out on the issue. Many voters are now convinced that Rahul Gandhi is a credible political leader after the yatra, but they still might prefer Modi as Prime Minister even as they reject the BJP in many of the state assembly elections. The issue of the Prime Ministerial face might have to be put off till the elections are and the results are announced. But going into the elections headless as it were will be fully exploited by Modi and the BJP. All the parties would want to avoid the hard decision of choosing the Prime Ministerial face because every one of them hopes that through the sheer spin of the dice, one of them could emerge as the surprise candidate for the Prime Minister’s post after the elections.

IDEOLOGY VERSUS POWER

The other main question is about ideology. The anti-BJP and anti-Modi opposition parties are presumed to be united in their opposition to BJP’s Hindutva politics and discrimination against religious minorities, especially the Muslims. In different degrees, this is indeed a common thread that brings together the opposition parties. But not all of them are die-hard secular ideologues. Many of them are shrewd enough to know that the secularism versus Hindutva plank might backfire and help the BJP, and that it would be wiser to focus on mis-governance of the BJP than on ideology.

NCP’s Sharad Pawar and JD (U)’s leader and Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar are seasoned politicians of the old school, who are not too interested in ideological opposition to Modi and the BJP. Their eyes are focused on gaining power. Between the two, Pawar might appear more principled in his opposition to the BJP’s Hindutva politics, but there is more political calculation in it than ideology. Nitish Kumar again a quintessential political player is not averse to playing ball with the BJP if the terms are in his favour, that is if the BJP would not disturb his chief ministerial throne in Bihar. West Bengal Chief Minister and Trinamool Congress (TMC) chief Mamata Banerjee belongs to the Pawar-Kumar school of politics, where the sole aim is to gain power. She is satisfied to be in power in West Bengal and she would not have any challenge on her turf. If BJP were to keep away from Bengal, then Banerjee has no quarrel with Modi. Like Nitish Kumar, Banerjee is with the opposition parties because the BJP threatens her position in the state.

Many would say that Rahul Gandhi is not the political weakling he was in 2019 and that post-Bharat Jodo Yatra he has been transformed into a credible people’s leader. But the jury is out on the issue. The majority of voters are now convinced that Rahul Gandhi is a credible political leader after the yatra

Tamil Nadu Chief Minister and DMK supremo M K Stalin belongs to a party which will not mind allying with the BJP if the power equation favours the north Indian right-wing Hindu party like the BJP. It is a myth that it is the liberal politics of Atal Bihari Vajpayee that persuaded the DMK to join Vajpayee’s BJP-led NDA government from 1998 to 2004. And the DMK had no quarrels in switching sides to Manmohan Singh’s Congress-led UPA government in 2004 and in 2009. Stalin is likely to be with the opposition parties because the BJP has these wild dreams of establishing itself in Tamil Nadu on its own. It will finally end up with either of the Dravidian parties as an ally.

It is Lalu Prasad Yadav’s and Bihar’s Deputy Chief Minister Tejashwi Yadav’s Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and the two communist parties – the CPI-M and the CPI – that are opposed to the BJP on the issue of secularism. One of the key electoral support bases for the RJD in Bihar is the Muslim constituency along with that of the Yadavs. And there is also the shrewd politics of the senior Yadav in creating a secular niche for the RJD in Bihar politics. He knows that it is the RJD’s secular credentials that has marginalised the Congress in Bihar, and he would not want to sacrifice that position. The communist parties are ideologically opposed to the BJP not just in terms of secularism, but also on economic policies. Critics might argue that the communist parties’ opposition to economic reform is hypocritical and that both Jyoti Basu and Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, the CPI-M Chief Ministers in West Bengal, had made their own compromises with the market economy. But these two Left parties still hold on to their ideological opposition to capitalism and the market economy.

Though ideas and ideologies are strong driving forces for political commitments, they are not strong enough to win elections because elections depend on many other factors and they are much more complex. So the idea of like-minded opposition parties joining and coming together to defeat Modi and the BJP is not a strong enough factor in an electoral strategy. All the parties have to acknowledge each other’s strong points, and play the alliance game accordingly. This boils down to the issue of seat-sharing in each state.

GAME OF ALLIANCE

The strategic part revolves around who is fighting who and where. The Congress and the BJP are pitted against each other in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Karnataka. Then there are states where the BJP is pitted against regional parties. It is pitted against Mamata Banerjee’s TMC in West Bengal, against Akhilesh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party (SP) in Uttar Pradesh, against Tejashwi Yadav’s RJD and Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) in Bihar, against AAP in Delhi.

Then there are states where both Congress and the BJP do not matter, and they include Tamil Nadu, where the Dravidian parties, the DMK and the AIADMK, are pitted against each other, and in Andhra Pradesh where Chief Minister YS Jagan Mohan Reddy’s YSRCP is involved in a direct fight against N Chandrababu Naidu’s TDP. The BJP’s strategy in these two states is to align with one of the two regional parties. In Telangana, the BJP is trying to emerge as the main opposition party against Chief Minister K Chandrashekar Rao’s Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) in Telangana and against Mamata Banerjee’s TMC in West Bengal.

It is Lalu Prasad Yadav’s and Bihar’s Deputy Chief Minister Tejashwi Yadav’s RJD and the two communist parties – the CPI-M and the CPI – that are opposed to the BJP on the issue of secularism. One of the key electoral support bases for the RJD in Bihar is the Muslim constituency along with that of the Yadavs

BJP is non-existent in Kerala in a significant sense as it is a fight between Congress-led UDF and CPI-M-led PDF there. Maharashtra has become complicated because of the split in Shiv Sena. Congress, Pawar’s NCP and Uddhav Thackeray’s Shiv Sena are pitted against the BJP and Eknath Shinde’s Shiv Sena. Punjab too has become complicated because of the surprise emergence of AAP in the assembly elections. What was once a fight between Congress and the Akali Dal has now become a triangular contest between AAP, Akali Dal and Congress. The BJP remains a marginal player in Punjab.

In the game of alliances, the BJP is not yet totally isolated. Not all of the non-BJP parties are with the anti-BJP group. Odisha Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik and his Biju Janata Dal (BJD) are a unique example which has refused to join either side. The Akali Dal walked out of the BJP-led NDA, but it has not joined the anti-BJP opposition. Three parties, the BRS in Telangana, TDP and YSRCP in Andhra Pradesh are again not with the BJP, officially, or with the anti-BJP parties. And that could be an advantage for the BJP because 62 Lok Sabha seats from these three states – Andhra Pradesh 25, Odisha 20, Telangana 17 – could tilt the tables when there is a close run-in.

The electoral map of India is very complicated both for the political parties themselves and for the voters. The BJP and the Congress, which are the nominal national parties in the field, are forced to rely on direct or indirect alliances with the regional parties. The BJP managed to move into the comfort zone of a simple majority in 2014 with 283 seats and that of an absolute majority with 303 seats in 2019. The BJP has a clear edge as a national party with its successive victories in 2014 and 2019. The position at the top, however comfortable, is a precarious one. The BJP can easily lose its perch even if there is no united opposition.

A BIG QUESTION

Whatever the political and electoral arithmetic, the big question of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections is whether Modi and BJP should get a third five-year term in 2024. Going by statistics, the BJP has reached the end of its tether as it were because 10 years in office is a long enough duration as it has happened with Manmohan Singh from 2004 to 2014. But the BJP’s luck can extend because of the state of the opposition parties which do not have much in common except the desire to dethrone Modi. It has been proved recently in Turkish presidential and parliamentary elections, when the ruling Justice and Development Party of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkiye won a fifth term in office, making it a 20 plus years run. Erdogan’s Justice and Development (AKP) party is known as an Islamist party and it is opposed to Turkish secularism that the founder of modern Turkey Mustafa Kemal Ataturk established in 1923, and many Turks especially in the interior areas were uncomfortable with the fanatical secularism of the Kemalist kind. There is a strong anti-secular sentiment running in India among the Hindus who form the majority of the country and of the voters, and it is possible that the majority would vote for Modi despite his acts of omission and commission in matters of governance.

Like Erdogan, Modi wants to deliver rapid economic development along with an anti-secular ideology. Though Modi has been advertising his achievements continuously – he told the US Congress in his speech during his recent visit to Washington that when he came to power in 2014, visited America and addressed the Congress India was the tenth largest economy in the world, but nine years later, in 2023, when he is addressing the Congress for a second time, India has moved to the fifth position. He was boasting of his achievement before the American lawmakers.

Maharashtra has become complicated because of the split in Shiv Sena. The Congress, Pawar’s NCP and Uddhav Thackeray’s Shiv Sena are pitted against the BJP and Eknath Shinde’s Shiv Sena

But the economy in India is not in a good position. Inflation is biting and the cost of living is rising though it is not yet a crisis, and Ruchir Sharma the market analyst, told an Indian news channel that India cannot hope to grow at the rate of 8 percent to 9 percent as it did between 2004 and 2009 during Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s first term in office because then the global economy was doing well but now the global economy is growing at a subdued rate of 2.5 percent to 3 percent, and therefore India can only grow at around 5 percent to 6 percent. Now that will not put India in the high economic growth orbit. The Reserve Bank of India has for the first time in three years expressed concern over inflation in the country, and that cannot be good news for Modi seeking a third term next year. India’s economic situation in 2013 was bad and it led to the defeat of the Manmohan Singh government in 2014 at the end of a 10-year term. Modi faces the same situation in 2023, going into the 2024 election. But it is possible for Modi to duck the trend and scrape through in 2024.

The opposition parties in their anxiety to sink differences among themselves have been harping on the need to defeat Modi in 2024, but it has not analysed the economic situation and it has not worked out an economic programme that will take India out of the present slowdown season. There is a need to offer jobs to people, nudge the private sector to invest and improve the manufacturing scene because that is where the jobs are. It is not going to be an easy task. Rahul Gandhi has been indulging in populist talk but he needs to bring to the table a carefully crafted economic programme. And the opposition parties have to focus on how badly Modi has handled the economy because there has been no private investment in these nine years, and the manufacturing sector has been in the doldrums during this period.

The economic populism of Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah may win Congress brownie points in the state, but it will not help the state’s economy. Modi has been indulging in economic populism these nine years in a guileful manner, and he is still doing it in the run-up to the 2024 election with free rations for 82 crore people, more than half the population of 140 plus crore.

In a way, the free ration tells a story of its own – how the people are on the edge even Modi and his cabinet colleagues boast that India is the fastest growing economy in the world. The opposition has a lot of homework to do if it wants to challenge Modi’s middling 10 years in office.

One thought on “Narendra Modi Versus The Rest”