A recent interview of Prime Minister Narendra Modi reignited conversations in diplomatic circles about reviving talks between India and China

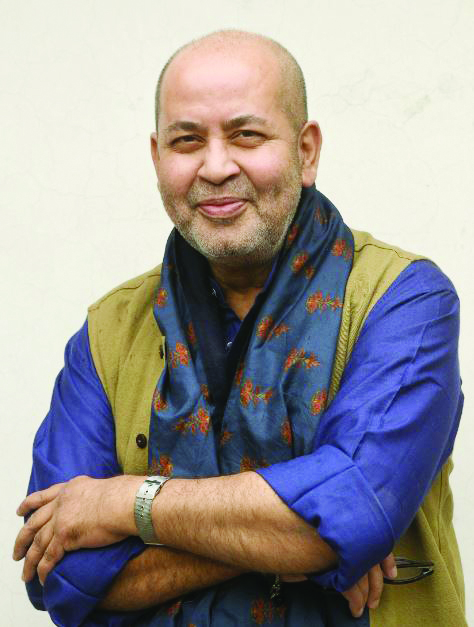

By Pranay Sharma

- China observers speculate that the stalled political dialogue between India and China will resume, if Modi returns to power

- China’s assertive policy in the region, since Xi Jinping has become the top most leader of China has raised serious concern about its rise

- QUAD, which has India, the US, Australia and Japan, is widely seen as a grouping put in place to deal with China’s aggressive rise

- China is India’s second largest trade partner and in 2023 the trade between the two sides reached US$ 136.2 billion, irrespective of the tensions at the border

A RECENT interview of Narendra Modi to the American magazine Newsweek has sparked off speculation in the diplomatic circles about an early resumption of the stalled dialogue between India and China at the highest political level.

Though officials and foreign ministers of the two countries have spoken to each other at regular intervals, talks at the highest political level have not taken place since 2019.

The “Chennai Connect” informal summit between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping was held in October 2019. This was the second such summit after the one held in China’s Wuhan where both leaders had met informally to discuss each other’s national goals and how that could mutually benefit the two countries.

However, further talks were stalled after China unilaterally moved its troops in Eastern Ladakh along the Line of Actual Control (LAC)—the informal border between the two sides in April 2020, violating the bilateral agreement and forcing India also to make heavy troops deployment on its side of the frontier a month later.

Several rounds of talks between the two armies and diplomats have so far failed to reduce the heavy deployment made by India and China to end the current face-off.

“For India, the relationship with China is important and significant,” Modi told Newsweek.

He added, “It is my belief that we need to urgently address the prolonged situation on our borders so that the abnormality in our bilateral interactions can be put behind us.”

Modi said, “Stable and peaceful relations between India and China are important for not just our two countries but the entire region and world. I hope and believe that through positive and constructive bilateral engagement at the diplomatic and military levels, we will be able to restore and sustain peace and tranquillity in our borders.”

GAUGING THE PULSE

Days before the Prime Minister’s remarks on China, the Foreign Minister and others from the Indian diplomatic establishment also expressed views that indicated a move towards rapprochement with Beijing was in the minds of leadership in Delhi.

Minister of External Affairs S Jaishankar while interacting with reporters on the rise of anti-Indian sentiments in the neighbourhood where China’s presence was growing said India’s relations with the neighbour was much better than what it was a decade back.

He also refused to be drawn into unnecessary controversies about China’s presence in the neighbourhood or about the tension between the two countries at the border by pointing out that at present India had an abnormal relation with China.

Jaishankar said “We have a challenging relationship with China. But this is a country which is today confident, which is capable of advancing and defending its interests, and in a competitive world, we will compete.”

The “Chennai Connect” informal summit between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping was held in October 2019. This was the second such summit after the one held in China’s Wuhan where both leaders had met informally to discuss each other’s national goals

The minister’s remarks suggested that while India was keen on normalising relations with China, it will not be done at the cost of India’s territorial integrity or interests. But China’s presence in the neighbourhood was a reality and India will have to maintain its position by competing with others.

Former Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale, who also served as India’s ambassador in Beijing and is widely considered as the country’s best expert on China, said India should adopt a two-legged approach to deal with China.

In an interview with Swarajya magazine Gokhale said, “The first leg is to build deterrence, and the second leg is to build dialogue.”

He added, “I think we just have to wait for another few months, let the electoral process run its course, and then the government, I’m sure, will deal with this as one of the priorities.”

It is now being widely speculated by China observers that the stalled political dialogue between India and China will resume, if Modi, who is expected to win a third consecutive victory as the country’s Prime Minister, returns to power.

SUMDORONG CHU STANDOFF

The evolving situation has also led many experts to draw a parallel with a similar situation in the mid-1980s that saw a prolonged border crisis between India and China.

In June, 1986, an Indian patrol found China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers on the banks of Sumdorong Chu rivulet in Arunachal Pradesh, an area that New Delhi always thought belonged to India.

Amid the stand-off China decided to increase its troops level in the area and built a helipad. While India decided to incorporate Arunachal Pradesh as a state of India from a Union territory.

Negotiations at different levels continued that led to the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s historic visit to China and wide-range of discussions with the Chinese supremo, Deng Xiaoping on how to lower temperature and stabilise the situation at the border.

But though Rajiv’s visit renewed contacts between the two sides at the highest political level that were stopped after the 1962 Sino-Indian border conflict, it took altogether nine years to resolve the Somdorung Chu stand-off.

It also led to the border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement of 1993. The document agreed that the India-China boundary question would be resolved through peaceful means and that the “ultimate solution” to the boundary question existed.

It was also agreed that force levels would be regulated and confidence-building-measures (CBMs) would be developed to maintain peace in areas along the LAC.

ECONOMIC AND REGIONAL REALITIES

Meanwhile, India and China have both changed significantly as has the regional and global security landscape. These changes have also had their impact on Sino-Indian relations.

China is today the second largest economy in the world, while India is its fifth largest. The Indo-Pacific region has also changed significantly as nearly 80 percent of global trade passes through its waters.

China’s rise is also not considered so peaceful by most countries. Its assertive policy in the region, since Xi Jinping has become the top most leader of China has raised serious concern about its rise among the neighbours. To push its maritime and territorial claims, China has got involved in disputes with a number of countries in the neighbourhood.

It has also come into India’s immediate neighbourhood and has entered into a competition with India in establishing influence over the South Asian countries by aggressively pushing its infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

But has also gone through some significant changes. Ending the era of coalition politics, for the past 10 years India has enjoyed a government that is in power on its own strength and does not depend on coalition partner’s approval to push policies that it has prioritised.

Another important development has also been in the steady growth of India’s relations with the United States. Though the relations between the two countries began to pick up in the aftermath of India’s nuclear tests in May 1998. Today the Indo-US bilateral ties have reached a new height as the two sides continue to expand their areas of cooperation for mutual benefit. They range from security and defence to trade and investment to high-tech and space to education and culture.

Most Indian diplomats acknowledge that the relation with the US is the most consequential in India’s foreign policy.

COUNTERBALANCE TO CHINA

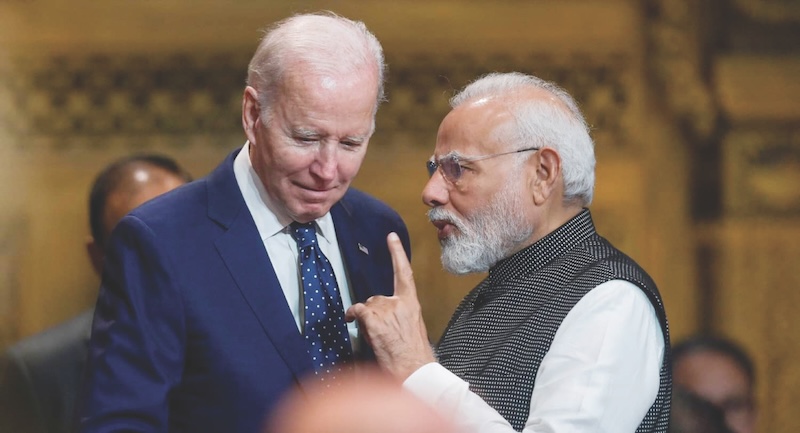

As the bipartisan support among both the Democratic Party and the Republicans have been built for stronger ties with India, the US’ relations with China have deteriorated steadily. American President Joe Biden has strengthened much of the policies that his predecessor republican President Donald Trump had initiated against China. Biden has also identified China as the country that poses an existential threat to America as it is the only nation that is capable of challenging US’s global hegemony.

Many experts believe that irrespective of India’s attractiveness as a huge market for American products and investment, the fundamental reason for the US to build strong ties with India is to use it as a counterweight to China.

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue known by its acronym QUAD and which has India, the US, Australia and Japan as its four members, is widely seen as grouping put in place to deal with the challenge China’s aggressive rise has posed in the Indo-Pacific region.

But India has argued that it is not directed against any particular country and the QUAD’s aim is to maintain an open, peaceful and stable Indo-Pacific.

Despite apprehensions about the growing closeness of India with the US from China and other detractors, India has successfully maintained its strong strategic ties with Russia, which continues to be its main weapons’ supplier. It has also widened its strategic options by building strong relations with countries across the globe and is today considered as the leader of the Global South.

It is not without significance that in recent weeks the US has taken the initiative to lower the temperature in its relations with China and look for areas where they can cooperate.

China has matched the US enthusiasm of normalising ties as the slow growth of its economy that began from the total shutdown during the Covid pandemic, is yet to pick up. If trade restrictions that America had put in place are eased, it is likely to help the Chinese economy to grow faster.

Biden’s reason for easing the tension with China may have been prompted by developments in other parts of the world like the ongoing wars between Russia and Ukraine and the one in Gaza by Israel against the Palestinians. At this juncture it will not be prudent for the US to open another front with China over Taiwan. This is widely believed to be one of the main reasons for lowering the temperature from the strained Sino-American ties.

FRICTION POINTS

For India, the current border face-off may be the most prominent issue with China but it is not the only irritant in Sino-Indian relations. Rather it can be seen as a manifestation of the growing tension in the ties.

A number of other issues including dissatisfaction over a growing trade imbalance and denial of market access for Indian products in the Chinese market have been building up for some years.

China is India’s second largest trade partner and in 2023 the trade between the two sides reached US$ 136.2 billion, irrespective of the tensions at the border.

Today the Indo-US bilateral ties have reached a new height as the two sides continue to expand their areas of cooperation for mutual benefit. They range from security and defence to trade and investment to high-tech and space to education and culture

Apart from the trade imbalance, there has been growing frustration in India at China’s regular attempts to block Indian efforts to get Pakistan-based terrorists who are known to have launched a series of attacks in India, designated as ‘global terrorist’ at the United Nations Security Council.

Though most countries have supported India’s candidature as a permanent member in an expanded UNSC, China has so far refused to endorse it. Many such actions of China have raised suspicion among Indian policy makers of Beijing’s attempt to block India’s rise at the global stage.

However, the biggest setback in Sino-Indian ties has perhaps been China’s unilateral decision to break the status quo at the LAC that has turned the India-China frontiers into a ‘hot border’ after years of peace.

India had maintained for a long time that normal relations between the two countries can only come after normalcy at the border is restored. Talks between the two sides have resulted in withdrawal of troops from some of the ‘flash points.’ But Chinese soldiers continue to be present in some more such areas.

A resumption of dialogue, whenever that may happen, will definitely try and find ways of clearing those remaining areas of Chinese soldiers. But there are several other issues that have to be addressed to normalise relations between the two countries.

The foremost issue will be over restoring trust and confidence that has been shattered by China’s April 2020 unilateral decision of breaking the agreements on maintaining peace and tranquillity at the border.

Indian diplomats pointed out that it is now obvious that the old template that guided the two sides to maintain peace at the border is no longer valid and a new one will be required before the Indian leadership thinks of resuming talks with China at the highest political level.

What form and shape it takes will be known in the coming days. But a resumption of political dialogue between India and China will certainly be an encouraging step forward for regional and global peace.