Mistakes have been made; but fortunately, not fatal. Overall, one can look back nine years with equanimity, if not a sense of celebration

By Sutanu Guru

- Every Prime Minister since Jawaharlal Nehru has made usually genuine attempts to forge better ties with Pakistan and China. Yet, both have remained hostile

- Modi met Xi more than a dozen times to pursue improved relations. But the clash between Indian and Chinese troops in Galwan in 2020 reignited mistrust

- In the long term, India must ensure that its economy is not dwarfed and overwhelmed by that of China, like it has been with the United States and Mexico

- Even if China wants, Pakistan cannot play the role of an effective pawn against India in the foreseeable future. Indian economy is 10 times that of Pakistan

A few weeks from now, the family of Colonel Suresh Babu and 20 other braves of the Indian armed forces will recall how their world turned upside down in 2020 even as India and the world were battling the once in a century Covid pandemic. The braves were killed defending sovereign Indian territory in the icy heights of Ladakh. The month of June also marks a tragic moment in the history of the armed forces. It was in early June 1984 that the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to evict Khalistani terrorists from the Golden Temple in Amritsar. Dozens of soldiers died even as the holiest of shrines for Sikhs was partially destroyed.

On the face of it, there is nothing common to the two events. Yet, they symbolise the threat that India faces from two implacably hostile neighbours China and Pakistan. Since the early 1980s when Zia Ul Haq was the military dictator of Pakistan, the country has been fomenting Khalistani separatism and terrorism. As recent events have shown, it continues to do so. China has been coveting Indian territory since 1950 when Mao Zedong became the unchallenged ruler of the Communist country. Under the current “President for Life” Xi Jinping who fashions himself as the second Mao, China continues to covet Indian territory. As subsequent analysis will reveal, one of them has become a pesky irritant with a capacity to launch a few terrors strikes within India. The other, the larger neighbour and the second largest economy in the world remains an existential threat.

FRIENDSHIP IS A MIRAGE

Nine years back, when the NDA regime took charge of the country and Narendra Modi became the Prime Minister; there was much hope for improved relations with the two neighbours based on pragmatic mutual interest. Nine years down the road, all such hopes have turned to ashes and dust. Modi had invited the then Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif along with leaders of other South Asian countries to his swearing in ceremony. He even made a surprise and unscheduled visit to Pakistan to meet Sharif. But as everyone knows, terror attacks didn’t stop; though the ferocity and frequency of such attacks on urban Indian centres did slow down considerably. Similarly, Modi met Xi more than a dozen times to pursue improved neighbourly relations. For a while, it seemed bonhomie would replace historical animosities. But the clash between Indian and Chinese troops in Galwan in Ladakh on June 20, 2020 reignited both animosities and mistrust.

How then does one measure the performance of the Narendra Modi regime over the last nine years when it comes to dealing with Pakistan and China? Three things need to be kept in mind while doing a dispassionate analysis. First, political rhetoric can never be a substitute for sober analysis. Sure, political rhetoric and trading of barbs and allegations are an integral part of any democracy. But that is not foreign policy. In the real world, foreign policy is the cold-blooded pursuit of strategic national interests behind the veneer of pious and politically correct statements. The second thing that needs to be kept in mind is the fact that China and Pakistan are not the sole arbiters or even targets of India’s foreign policy. There is a much wider world beyond the two to engage with. Third, every Prime Minister since Jawaharlal Nehru has made usually genuine attempts to forge better tie with Pakistan and China. Yet, both have remained implacably hostile for the last seven decades. At the end of the day, the question that needs to be answered is: Has the current regime adequately used domestic and foreign policy instruments to successfully tackle the threats posed by Pakistan and China? Only the naïve would still believe that a genuine friendship with the two remains in the realm of a possibility.

THE REAL THREAT IS CHINA

The real strategic threat posed to India is by China. It is already the second largest economy in the world with arguably the second most powerful military. Any hopes that the western countries like the United States had of a more nuanced China emerging after engaging deeply with democracies have vanished. Xi Jinping has made it clear that the authoritarian state is determined to restore the “historically rightful status of China”. Despite promises of retaining the “unique character” of Hong Kong, it has ruthlessly crushed all forces of democracy and individual rights in Hong Kong. It has become increasingly belligerent over Taiwan and now makes public threats of using military muscle to “reintegrate” Taiwan with China. Southeast Asian countries like Philippines appear helpless when confronted with a bullying China. Worse, many commentators in Asia wonder if the United States has the will and the capacity to prevent China from completely dominating Asia.

China has been coveting Indian territory since 1950 when Mao Zedong became the unchallenged ruler of the Communist country. Under the current “President for Life” Xi Jinping who fashions himself as the second Mao, China continues to covet Indian territory

It is against this backdrop that Indian foreign policy has to deal with China. What is the first and immediate goal? To prevent China from capturing any territory in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh (which China fancifully describes as South Tibet). Sober minds in Delhi have concluded that China’s lust for Indian territory will not fade away in the foreseeable future. But the manner in which the Indian government has reacted since 2020 (forget the political rhetoric) has made the leaders of China painfully aware that a walkover of the kind achieved in 1962 is no longer possible. Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty is a cliched proverb. But it is apt when it comes to India’s borders with China. The furious pace at which India has been investing in border infrastructure since 2014 will also act as an effective deterrent.

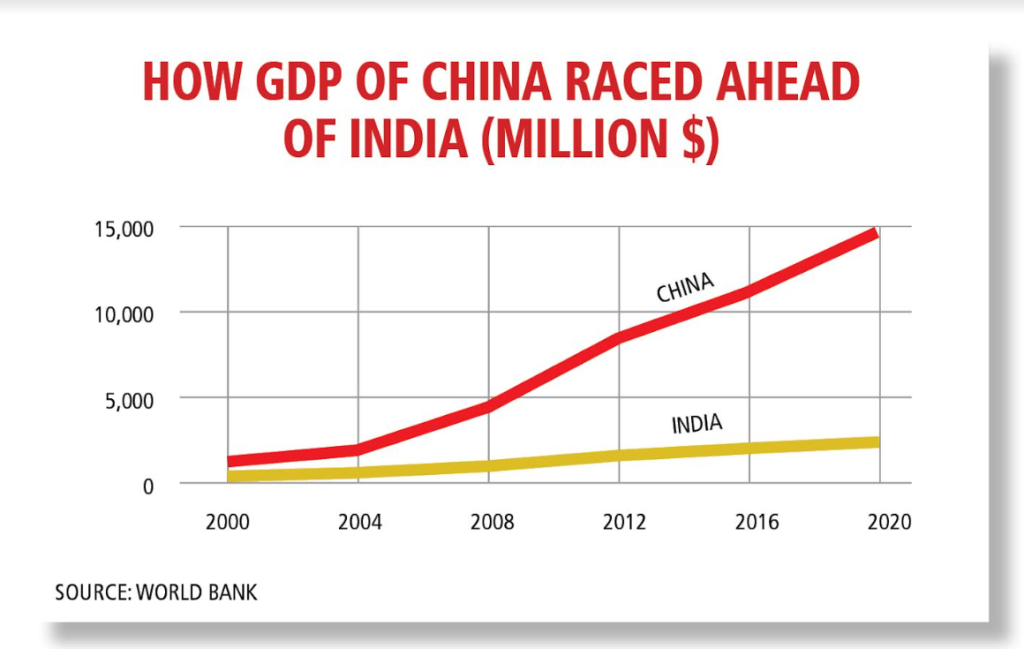

The real strategic threat is economic. In the medium to long term, India must ensure that its economy is not dwarfed and overwhelmed by that of China, like it has been with the United States and Mexico for over a century. The first graph shows how the Chinese economy has raced ahead of India in the 21st century. As the chart indicates, the GDP of China was two and half times larger than India at the turn of the century. By 2020, it was almost five times larger. China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2000 and has since become the manufacturing and export hub of the world. India too has grown at a decent rate, but nowhere near the blistering pace maintained by China. This has enabled China to make massive investments to modernise its military. It has also enabled China to “lend” money to countries like Myanmar, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and encircle India with its “string of pearls” approach. Pakistan, of course, is a de facto client state of China. Many foreign policy commentators wonder how the policy establishment failed see this emerging threat from China. Or how it failed to do anything substantive even if it were aware what a huge Chinese economy could do to undermine India’s interests in its immediate neighbourhood. The good news for India is that China has done what it could. For one, everyone agrees that the GDP growth rate of India will surpass that of China for the next decade or so. By then, even foolhardy “Imperialists” in Beijing will know that defeating India either militarily or economically would be inconceivable. Second, citizens in countries like Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh have realised that far from being a “friend”, China is driving their countries into a debt trap and economic misery. But before that, India needs to seriously tackle any strategic economic threat: that of exports from China swamping and drowning the Indian economy.

ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES

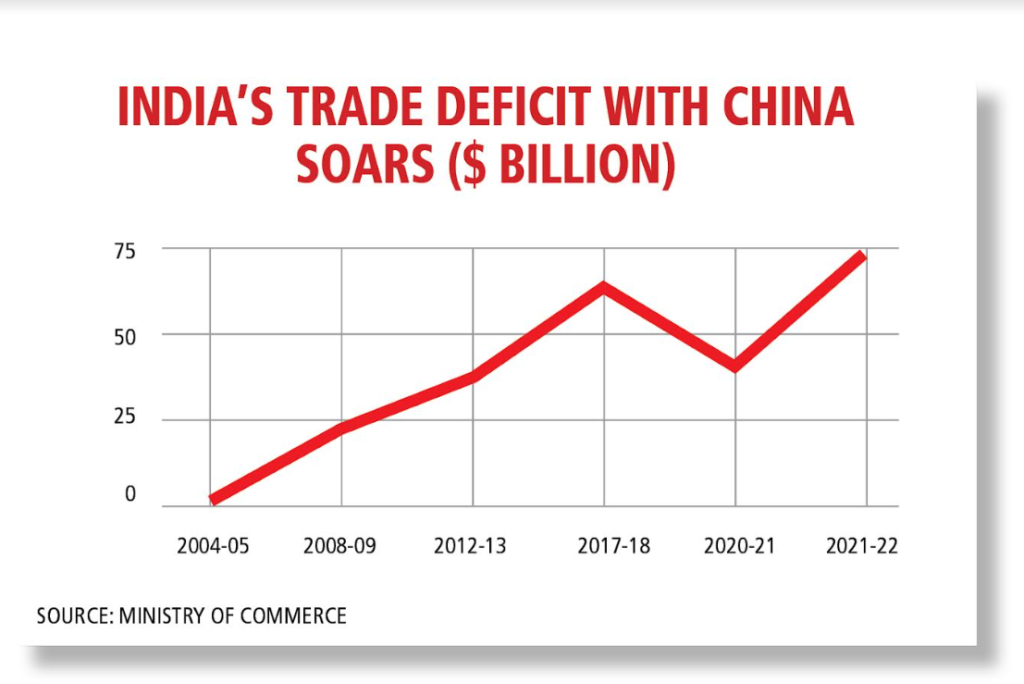

The chart above makes it clear that India needs to take urgent steps to control the trade deficit with China. In some ways, the Indian economy is paying dollars to China every year at a massive rate. Common sense dictates that it is unwise to finance someone who behaves like an enemy. The year 2020-21 is unusual because the Indian economy actually contracted because of the Covid pandemic. Look at it another way: India has transferred about 500 billion USD to China over the last decade or so. If one ignores rhetoric, the ballooning trade deficit is understandable. After all, China is the manufacturing hub of the world and when an economy like India grows at 6% or more a year, imports from China are bound to soar. Yet, neglect has resulted in cheap Chinese goods killing domestic industry across sectors and snatching away millions of possible jobs. To that extent, the Make in India initiative of this regime makes a lot of sense, particularly the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme launched a few years ago. Critics call it a failure. But such policy changes take close to a decade for the benefits to emerge. Look at mobile phone exports to see the promise and power of policies like PLI. In 2017-18, India exported mobile phones worth about 1 billion USD. By 2022-23, they had grown ten times to 11 billion USD. Another global development could help India: the urge of global companies to shift production bases away from China in a gradual manner.

Xi Jinping has made it clear that the authoritarian state is determined to restore the “historically rightful status of China”. Despite promises of retaining the “unique character” of Hong Kong, it has ruthlessly crushed all forces of democracy and individual rights in Hong Kong. It has become increasingly belligerent over Taiwan and now makes public threats of using military muscle to “reintegrate” Taiwan with China

These economic aspects are closely interlinked with geopolitics. Perhaps the biggest success of this regime in tackling China has been a genuine revival of the Quad-a strategic partnership between the United States, India, Japan and Australia. The Quad is not a magic bullet; but it does send a powerful message to China that India is not isolated in case China adopts a military option. In any case, for all intent and purposes, the immediate focus of China is the “reintegration” of Taiwan. That is not possible without a military invasion. In the event, whether the US steps in to help Taiwan or not, China cannot fight two military conflicts at a one go: one to capture Taiwan and the other to gobble up Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh. Foreign policy is often about sending the right signals. India has been sending the right signals to China.

WHAT ABOUT PAKISTAN?

That brings the analysis to that pesky irritant of a neighbour called Pakistan. For decades, China has successfully used Pakistan as a strategic asset to keep India tangled so that taming it could become easier. It didn’t help that most of the world tended to equate Pakistan with India and project a “South Asian” narrative. But only academics do that in India. Arguably the biggest foreign policy success of this regime has been the decisive manner in which India has de-hyphenated itself from Pakistan. Sure, some countries, peaceniks, human rights activists and habitual India critics make the occasional noise about Kashmir. But the world has moved on after Article 370 was abrogated in 2019.

Two surgical strikes have also allayed fears of any nuclear reprisal from Pakistan if Indian forces kill terrorists within Pakistani borders. More importantly, Pakistan itself is facing such an existential crisis of its own that it is in no position to threaten India. The economy is virtually bankrupt and would default on external debt if China, Saudi Arabia and the UAE do not roll over past loans. Inflation is in excess of 35%, the interest rate is a staggering 21% and the Pakistani Rupee’s value is plummeting towards Rs 300 to a dollar. Not very long ago, its currency was stronger than that of the Indian Rupee. Credible media outlets in Pakistan report how at least 10 citizens die each day in stampedes for “Atta” or wheat flour.

To make things worse, political unrest and instability have virtually crippled the country. Imran Khan and his supporters have been on a rampage ever since was ousted in 2022. He has done what no one in Pakistan had ever done: divide the military and the “establishment” into two opposing camps. In a way, the political executive, Imran Khan, the Supreme Court and the armed forces are at war with each other. Even if China wants, Pakistan cannot play the role of an effective pawn against India in the foreseeable future. The Indian economy is already 10 times that of Pakistan. By the end of this decade, the gap would make Pakistan irrelevant. Except the occasional terror strike, of course. Even here, the regime has ensured that no major civilian area in an urban centre has been targeted by suicide attacks. 26/11 is a bad memory.

China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2000 and has since become the manufacturing and export hub of the world. India too has grown at a decent rate, but nowhere near the blistering pace maintained by China. This has enabled China to make massive investments to modernise its military. It has also enabled China to “lend” money to countries like Myanmar, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and encircle India with its “string of pearls” approach

Critics of the regime would undoubtedly have valid reasons to criticise some aspects of its approach towards China and Pakistan. All regimes make mistakes. But perhaps it would be safe to say that when it comes to tackling China and Pakistan, the regime has not made fatal or strategically ruinous mistakes.