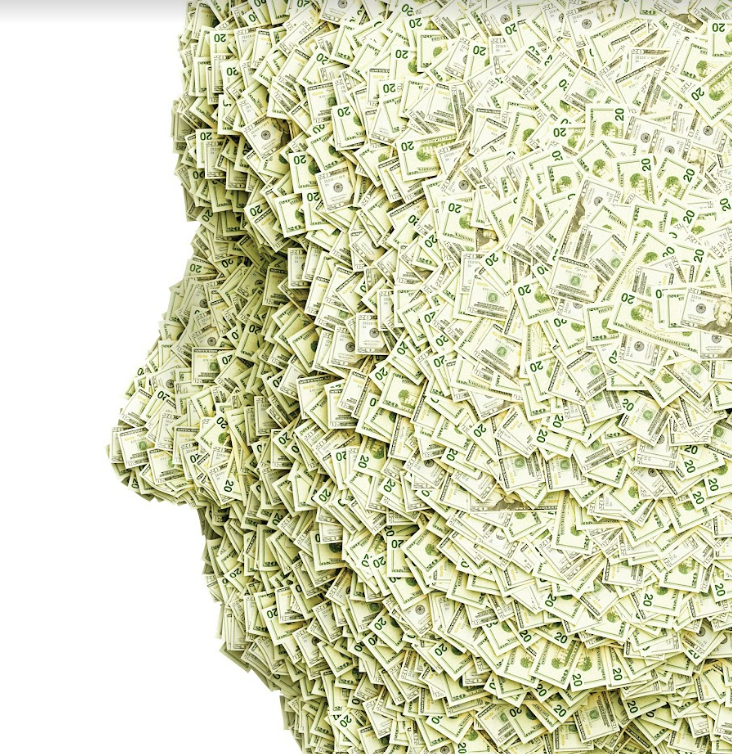

Since the past decade, executive salaries shot up by $500,000 a year, and workers’ wages by a mere $1,303. ‘Greedflation’ is how AFL-CIO, America’s largest union, dubs this trend. CEO greed, as opposed to working people’s demand, is the cause for the ongoing runaway inflation

By Alam Srinivas

- In the past decade, executive salaries shot up by $500,000 a year, and workers’ wages by a mere $1,303

- The demand for top managerial skills shifted from those specific to firms and sectors to generalised ones. Hence, there was intense competition for talent

- 3 of the most underrated corporate heads – Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, and Jamie Dimon – were also among the most overrated

- As disruptions in businesses become frequent due to technology, finance, and products, the top people are valued at a higher scale

In 2021, Amazon’s CEO earned almost 6,500 times the median salary of the company’s remaining employees. At Expedia, a tech company, the ratio was 2,897:1; at McDonald’s 2,251:1, and; 1,711:1 at Intel.

AFL-CIO’s annual Executive Paywatch Report revealed that the average annual compensation for CEOs of top 500 US companies was $18.3 million in 2021, or 324 times the median worker’s pay. The ratio was higher than the figures in 2020 (299:1) and 2019 (264:1).

GREED GRAB

Since 1978, when the booty for corner room’s occupants went into an upward tizzy, estimates the Economic Policy Institute, “CEO pay has increased by 1,322%… compared with an 18% bump for the typical worker”. In the past decade, executive salaries shot up by $500,000 a year, and workers’ wages by a mere $1,303. ‘Greedflation’ is how AFL-CIO, America’s largest union, dubs this trend. CEO greed, as opposed to working people’s demand, is the cause for the ongoing runaway inflation. No wonder, High Pay Center, a think tank, finds that people are convinced that CEOs are overpaid.

For example, six out of 10 people in the UK feel that the differential between CEOs and workers cannot be more than 10 times. Peter Drucker, a renowned management expert, estimated that the ratio should be 20:1. “The compensation of a tiny group – not more than 1,000 people – at the top of a very small number of giant companies… offends the sense of justice of many, indeed the majority of management people themselves,” he wrote. Well, it’s true – most of us think CEOs are overpaid, and don’t deserve what they get.

In 2021, Amazon’s CEO earned almost 6,500 times the median salary of the company’s remaining employees. At Expedia, a tech company, the ratio was 2,897:1; at McDonald’s 2,251:1, and; 1,711:1 at Intel

Consider yet another extreme situation. At the first sign of trouble, the average employees, people like you and I, are the first to get pink-slipped. Sacking jobs is invariably the first step taken to slash costs. The CEO is among the last to go, if she ever does. Even if the head is finally cut off, the top managers are able to find new, mostly more lucrative, options. We, the middle and lower rungs, have to settle for lower salaries, less responsibilities, or remain without work for months. This scenario is panning out, right now, even as you read this piece.

RECENT DOWNSIZING

On November 15, Amazon announced that it would put 10,000 employees on the streets. Poor economic outlook and weak corporate performance – in this year’s third quarter, revenues were up 15% and operating profits plummeted by almost 50% — are the reasons to keep a lower head count.

Meta (Facebook) decided to fire 11,000 people, or 13% of its workforce. Its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, lamented that he wrongly assumed that post-Covid acceleration in revenues would be permanent. “Unfortunately, this did not play out the way I expected,” he wrote in a post. Eleven thousand suffered as a consequence.

The most chaotic and scary narrative emerged from Twitter, in the form of 4,400 of the 5,500 global contract employees, rather than 280 characters. To be fair (pun intended), the new owner, Elon Musk, fired the CEO, along with others. He ended the era of remote work and ejected those who disagreed with him. Musk warned that Twitter faced possible bankruptcy, and the “road ahead is arduous”.

In August, Snap, Snapchat’s parent, laid off 20% of its employees. CEO Evan Spiegel said he was “deeply sorry” but the changes were crucial “to ensure the long-term success of our business”. Carvana fired its 2500 employees via Zoom. The company has cited a slump in auto sales as the main driver for this layoff.

Peloton, the fitness company, has fired more than 35% (approx. 3370 employees) of its workforce this year. It was a result of the rapid drop in sales after its record growth during the at-home workout boom during the pandemic. Ford announced laying off 2,000 salaried workers and 1,000 contract workers across the US, Canada and India. Streaming giant Netflix has laid off about 2% of its workforce, cited to shrinking subscriber count.

WHY IS A BIG GAP?

CEOs are treated differently than the remaining employees, both in terms of compensation and survival. The obvious question: why? Let’s first accept a not-so-evident truth. These are emotional conclusions, and cut both ways. A 2019 survey in the US found that three of the most underrated corporate heads – Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Apple’s Tim Cook, and JP Morgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon – were also among the most overrated. At one level, we feel that CEO compensations are unjustified and, at another, they are. Possibly, the best way is to judge them on quantitative parameters. Or, is it?

Just to be on the side of the richer and better-paid people, studies indicate that the differential between CEO compensation and media worker’s salary may be skewed for various reasons. The data for the former, for example, includes “non-salary” benefits like bonus, retirement payments, stock options and grants, and severance. In the latter’s case, only the salary is considered. The ratios can appear higher in case the top person is paid one-time compensation, or she works at a firm with a sizable number of part-time, contractual, or foreign employees, who earn lower wages.

A few studies conclude that the monies paid to those in the corner rooms are in sync with shareholders’ returns. Steve Kaplan of Chicago Booth and Joshua Rauh of Stanford find that the “highest-paid CEOs in terms of realised pay – top 20% out of 1,700 firms – generated three-year stock returns that were 60% higher than those of other firms in their industries. The bottom 20%… underperformed other companies in their industries by 20%”. In fact, states an article (February 2022) on ‘harvarde du,’ during the past decade CEO pay “trailed TSR (Total Shareholder Return) performance by a negative 10%”.

Historically too, this is true, according to some research. An article (November 2016) on hbr.org explains that “a compelling historical analysis of 18,000 firms over 60 years” proved that financial performances, like returns on sales and assets, increased with time in the US, as did CEO compensations. Between 1980 and 2003, state a couple of researchers, average CEO pay was up by six times. So was the market capitalization of the firms. Kaplan argues against the statement of Bernie Sanders, US Presidential candidate in 2016, that “there is something wrong with the system”.

In 2016, Luis Garicano of the London School of Economics and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg of Princeton University described firms as “knowledge hierarchies”. Thus, CEOs specialise in problem-solving, and earn much more than others, who engage in production. It’s dictated by the demand-supply curve – talent at the top is scarce, talented CEOs are rare and, according to Marko Terviö of Aalto University in Finland, this can “lead to large differences in pay”. As disruptions in businesses become frequent due to technology, finance, and products, the top people are valued at a higher scale.

Over the past few decades, states an article on mit.edu, the demand for top managerial skills shifted from those specific to firms and sectors to generalised ones. Hence, there was intense competition for talent. In the case of human resources, as opposed to products and services, the tussle skyrocketed the salaries for the top-level people. In addition, adds the same piece, “stricter corporate governance and improved monitoring of CEOs by boards” pushed up pay as top talent had to be compensated for increasing job instability. Since CEOs can be kicked out easily, they demand more money.

STOCK OPTIONS

Don’t forget that the major component of higher CEO net income is in the form of stock options or stock grants, which are linked to corporate performance. Lawrence Mishel of Economic Policy Institute calculates this figure to be 85% of CEO compensation. Especially in the 1990s, the move towards options, which gives CEOs the option to buy shares of their companies, became popular due to “several tax and accounting changes that made them more valuable to the executive and less costly to the firm”. In the 2000s, legal changes in the US made grants, i.e., actual allotment of shares, more attractive.

CEOs value stocks, either as options or grants, only if the share prices move up. If stock value stagnates or comes down, a CEO seems worthless for a firm and, for the CEO, the shares are irrelevant. Under a new ‘Say on Pay’ law in the US, shareholders can vote on executive pay packages

Both options and grants are performance-based, both for the firms and CEOs. Companies wish to pay more via stocks, only if they become more profitable or their stock prices zoom. CEOs value stocks, either as options or grants, only if the share prices move up. If stock value stagnates or comes down, a CEO seems worthless for a firm and, for the CEO, the shares are irrelevant. Under a new ‘Say on Pay’ law in the US, shareholders can vote on executive pay packages. Obviously, investors reward CEOs, who increase their wealth. Thus, CEO’s pay is directly linked to achieving crucial financial and other targets.

SAY ON PAY

Like most noble and well-meaning initiatives, ‘Say on Pay’, and payments through stocks have several negatives. The partial truth is that on a selective basis, stocks don’t work in reality. A recent study finds that “most overpaid CEOs” in 10 US companies destroy shareholders’ wealth. In the past four years, researchers conclude that on an aggregate basis, the returns for these 10 firms… lag the S&P 500 by 14.3 percentage points, posting an overall loss in value of over 11%”. To prevent similar scenarios, CEOs can resort to illegal and unethical practices to safeguard their incomes.

The most obvious one is that topmost executives “manipulate performance measures that are used to determine their pay”. An older study (of over 1,000 companies) by Amit Seru of Chicago Booth, Adair Morse of Berkeley and Vikram Nanda of Georgia Tech concludes, “Up to 30% of the fluctuation of incentive pay based on performance can be explained by rigged performance measures.” They add, “Incentive contracts are at best only partially effective in compensating for weak corporate governance.” An article (June 2021) on Investopedia.com agrees, “Options can… prompt top managers to manipulate the numbers to make sure the short-term targets are met.”

Worse, the piece explains that options (and stock grants) incentivize senior-most executives to shore up stock prices, by hook or by crook, “so that options will stay in the money”. This logically “encourages executives to focus exclusively on the next quarter and ignore shareholders’ longer-term interests”. The backdating and ‘spring-loading’ of options became common practices in the 2000s. University of Iowa’s Erik Lie discovered that “companies granted stock options to executives just before their stock prices spiked”. This was part of the options backdating scandal in the US in 2005-06.

Internal investigations by firms, and external ones by authorities “led to dozens of financial restatements and executive dismissals. Although only 12 executives ultimately received criminal sentences, and only five were given prison terms”, as per an article on chicagobooth.edu. Spring loading was easier – companies “awarded options (to CEOs and other senior executives) right before the release of positive news”. In the case of stock grants, the dates can be “chosen ex‐post to minimise the strike price of at‐the‐money options and maximise their value to executives”. In short, both options and grants can be rigged.

Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried of Harvard Law School, therefore, emphasise the “managerial power hypothesis” in their book, Pay Without Performance. CEOs can “extract rents” in the form of higher perks and incentives because they are “friends” with board directors, and have a “say in setting… perks”, or directors don’t know enough about the operations of the firms. This can lead to “stealth compensation”, which are either hidden from investors and outsiders, or are “difficult… to discern”. This has changed in the past two decades due to “outlawed practices” and greater disclosure norms.

CEO greed, as opposed to working people’s demand, is the cause for the ongoing runaway inflation. No wonder, High Pay Center, a think tank, finds that people are convinced that CEOs are overpaid

Disclosures resulted in interesting possibilities. As US firms need to divulge the pay ratio between CEOs and average workers, the information becomes a tool for policy makers. The city of Portland, Oregon “levies a 10 percent surtax on firms that surpass (a ratio of 100:1). It rises to 25 percent on firms with pay gaps exceeding 250 to 1.” Similar “pay gap bills” are in play in California, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Rhode Island. Institutional investors believe in this golden ratio. ERAPF, which handles France’s public pension fund, has set a “socially acceptable maximum amount of total (CEO) remuneration” – 100 times the minimum salary.

At the end of the day, something has to give. CEO compensations cannot hold for long. As the foreword of a study (2018), Why and how investors can respond to income inequality, by the UN Principles for Responsible Investment states, “Institutional investors have increasingly begun to realize that inequality has the potential to negatively impact institutional investors’ portfolios, increase financial and social system level instability; lower output and slow economic growth; and contribute to the rise of nationalistic populism and tendencies toward isolationism and protectionism.”

One thought on “Greedflation Drives Inflation”